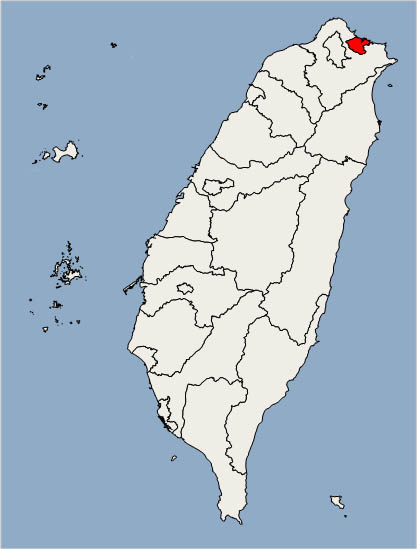

On a rock face in Keelung in Taiwan is a message in Chinese characters.

|

These characters were written in 1884 by a Chinese navy officer to pay respect to a young English engineer, who was hired to build the first machine-operated coal mine owned by Chˇ¦ing government.

Apparently it refers to David Tyzack who went there to improve the output of the local coal mine. Below is the story of Badou Zi (in English, Coal Harbour), where British technician Zhai Sa (David Tyzack) came in 1874 to devise and install the first official coal mining machinery and who was instrumental in the railway which carried coal to the harbour.

Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet, GCMG (20 February 1835 – 20 September 1911), was a British consular official in China, who served as the second Inspector-General of China's Imperial Maritime Custom Service (IMCS) from 1863 to 1911. He is credited with preventing a war with Britain in 1876, and he and his London representative, James Duncan Campbell, helped bring about peace after a French attack on the Chinese navy in Fuzhou in 1884. He wrote frequently to James Campbell. Here is the excerpt which started this story off.

Dear Campbell,

I have telegraphed to you today:

1. To send me an experienced mining engineer to examine (the Formosan) coalfields, advise scientifically as to their working and superintend practically paying mining operations (I used these adjectives and adverbs to drive it into you that we want a man who is at once learned and practical — one who has studied and worked: and I used the word "paying" to suggest that we want a man to work in such a way as to make mines pay). I told you to look sharp and strike quickly, for the iron is hot (i.e. the Chinese want us to work the Keelung Mines, and I don't want to give them time to change their minds) and to direct him to bring out estimates and plans for extracting coal perpendicularly and horizontally: and to keep his own counsel. I hope before this letter reaches you, your man will have started for China. I said nothing about terms, leaving it to you to fix them I want to say to you, by the way, that, when I don't name terms I leave the settling of them entirely in your hands.

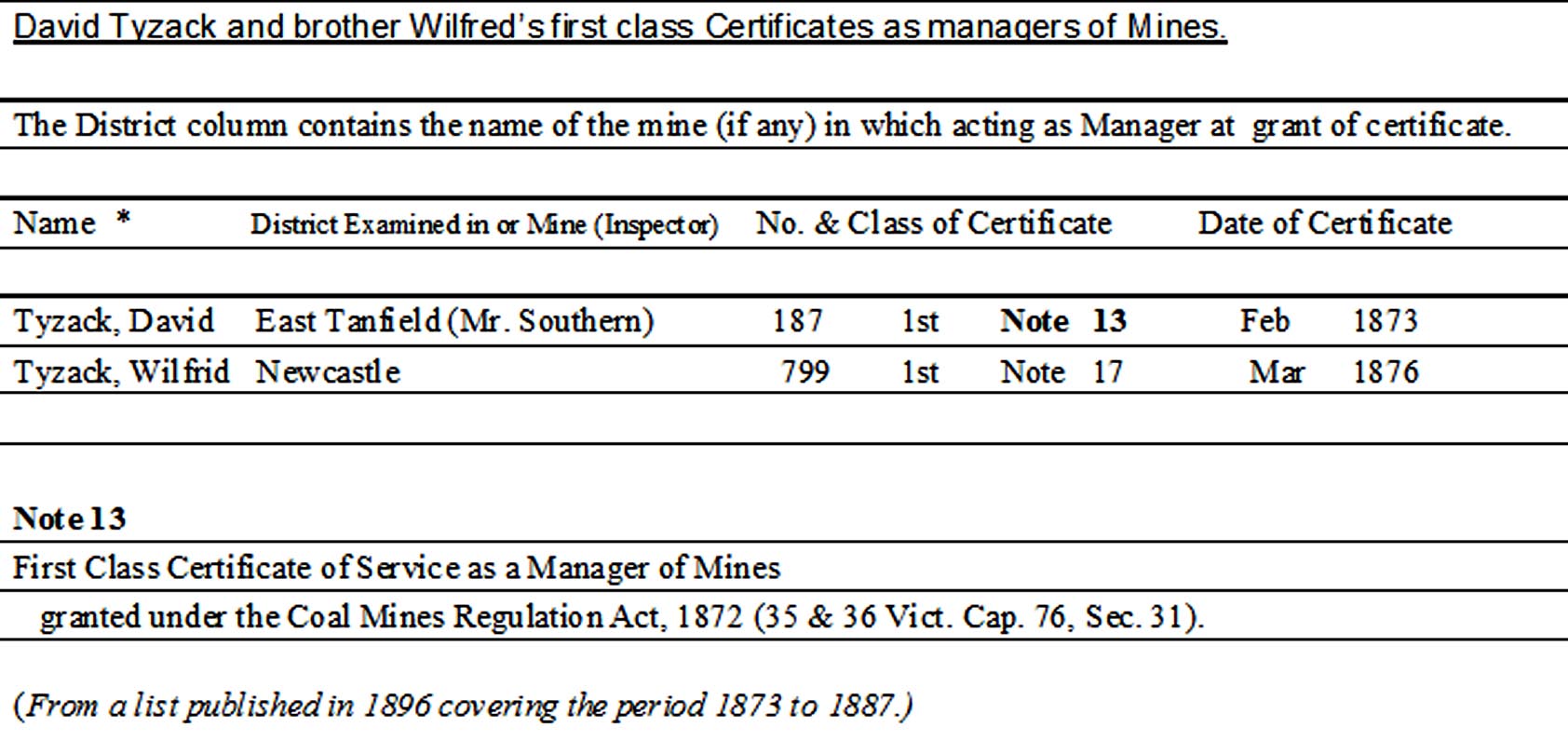

James Duncan Campbell, Hart’s London Office manager, immediately advertised the opportunity in a national newspaper. His advert appeared on 31st October 1874; it sought someone to serve as a mine engineer in a distant country. The advertisement found fierce competition and produced more than 40 candidates. At the time Benjamin Disraeli had just won the general election, and among those elected were Alexander Macdonald and Thomas Burt, both former coal miners and among the first working class Members of Parliament.

David was then a coal mine manager with a first class certificate who had never left England. The journey from Britain was long, although the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had made it easier. The Taiwanese coast wrecked vessels and then they were plundered and foreign property stolen. The British government decided that the best way to protect their shipwrecked seamen and vessels was to send men-of-war to patrol this coast. One vessel that carried out periodic patrols was the HMS Dwarf, captained by Bonham Ward Bax. During 1871-1874, the ship not only regularly visited the ports of Taiwan, standing by to rescue shipwrecked mariners, but also providing escort for English missionaries travelling to hostile areas. By the presence of his warship and displaying superior force, Captain Bax kept the ruling authorities in line while intimidating xenophobic brigands. Indeed, the monthly patrol of the British warships not only bolstered the confidence of English missionaries, but also helped calm the nerves of Taiwan's Christianized natives. Unfailing support was rendered by British diplomats, and wealthy English merchants. Ł103 was given by Donald Matheson of Tait & Co. in Tamsui to the Reverend George L. Mackay so that the latter could recruit a Canadian medical doctor. Most of the English companies in Taiwan imported opium, textiles, gunpow¬der, and saltpeter and bought Taiwanese camphor, tea, sugar, silver, sulphur, and rice. One foreign firm dominated nineteenth-century Taiwan trade: Jardine, Matheson & Co., headquartered in Hong Kong. Even before trade with Taiwan was legalized, Jardine had brought large quantities of Bengali opium to the island.

| On Tyzack’s arrival Keelung’s British Customs officers said: “Welcome to Coal Harbour!” Tyzack was introduced to the Fuzhou Ship Councils. The Customs officers warned Tyzack that the local people there were superstitious, and there were some incompetent officials, who paid more attention to their own safety. A man named Xu Tingrui was made responsible for the protection and companionship of Tyzack. Fortunately Xu Tingrui was English speaking. Tyzack found local coal mining was still carried out in a primitive way, but the people there were very friendly, greeting Tyzack with tea. |

When he was settled, he now had the big task of writing the plan of what he must do in the mine.

After intense discussions, Shen Baozhen agreed and the plan was agreed to be carried out according to the proposed submission.

Xu Tingrui briefed Tyzack on the newly appointed governor of Fujian, Ding Richang. Ding Richang had met with the people who were petitioning local officials. They complained that mining has destroyed feng shui, and so should be stopped. Ding addressed the people. Ding Richang pointed out vehemently that foreign powers were about to invade, and that the State was not protected. Where then is feng shui?

After leaving Ding Richang, Xu Tingrui invited Tyzack on a night visit showing him how "shipping lights" and the Keelung Ghost Festival enhanced the Keelung area where many foreigners will come. He said that Chinese habitually used water lanterns in such places.

Pastor Rev. George Mackay came about then to preach at Coal Harbour. At the time Tyzack writes of an epidemic of fever. Hundreds of workers were killed, British engineers were also infected. Mackay ran a clinic where he cared for many patients. Around this time 1878 Tyzack describes to Mackay the size and production capacity of the mine.

During 1880 Mackay invited the Tyzacks home for dinner. Tyzack detects a new breed at Fuzhou. He senses a suspicion of corruption, he is discouraged, he finds the garrison has become unfriendly. His new wife is worried. Mackay returns to Tamsui to talk to the British consul. The British Consul and Zhang Meng Yuan meet. They agree Coal Harbour mine is in a good situation today, thanks to Tyzack, the Chinese government should praise him. He reminds Zhang of past official corruption that may raise problems. Zhang is noncommittal. Following all this a new figure appears on the scene, Liu ao. He is charged with improving the income of the garrison and starts by making inspections of the Navy Yard and calculating various mine costs. He talks to a representative called Chuan zheng who says that Chinese engineers are now trained to operate the mines, and recommends dismissal of the foreign workers, to reduce costs.

So it was that Liu ao arranges that Tyzack is now dismissed and must return to England. Next we find in 1884 Tyzack and his wife are now on board the ship and leaving the dockside at Taiwan. They wave to Mackay and the boat sets off.

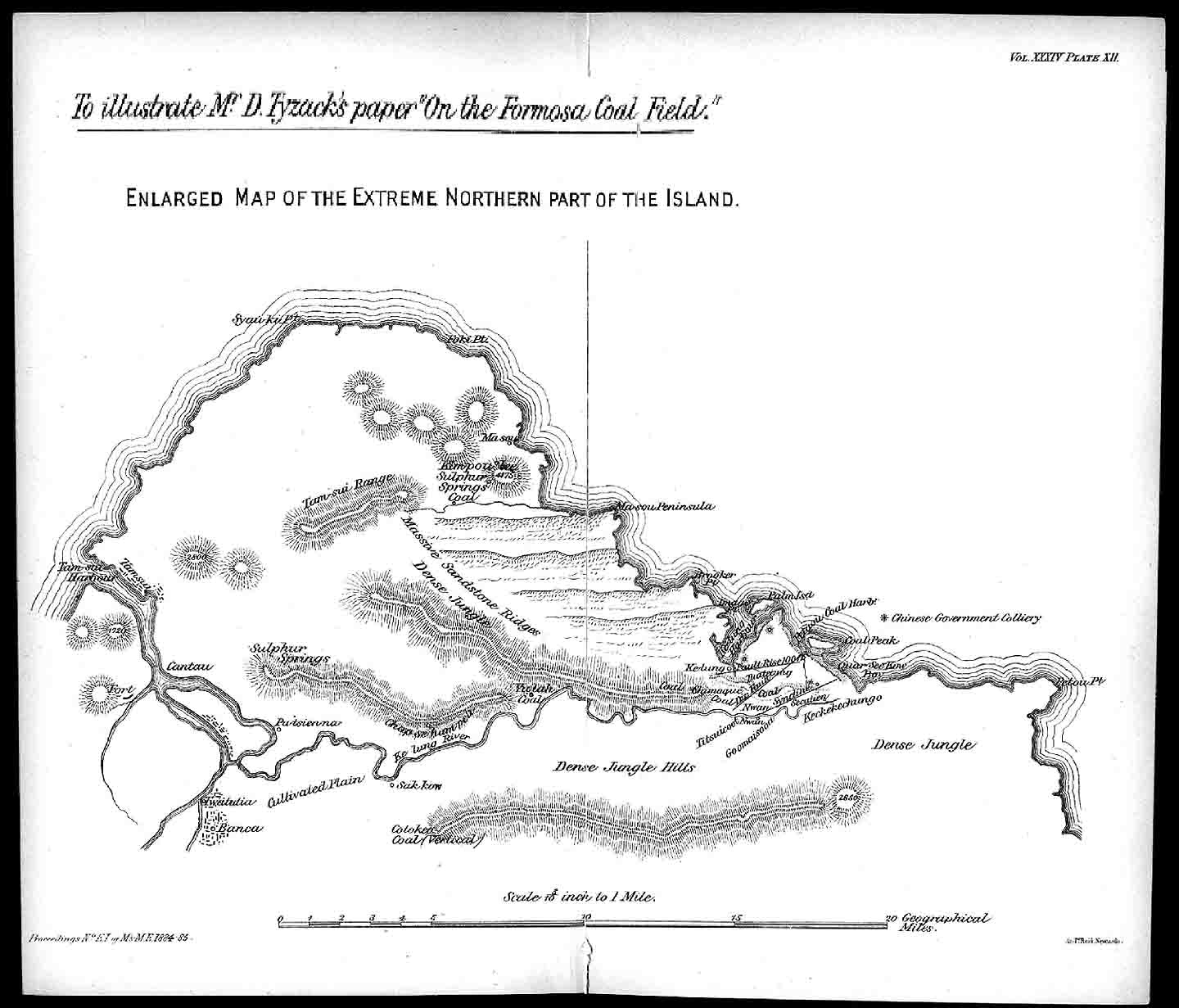

| Tyzack makes his speech about Keelung, Formosa at a formal dinner: “Notes on the coal-fields and coal-mining operations in north Formosa (China). Transactions, North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers 34 (1884-5): Plate XII. Tyzack, back in Britain, remained as a mining engineer and a chartered member of the Institute of mining. His membership was retained and recorded until 1897. I have no record of his death but it could be the reason for cessation of membership. But domestic things happened before then. |

A few years after they returned Isabella was taken ill. (I do not know her illness but she was sent to Devon for a cure so it may have been what was then called consumption, ie Tuberculosis). However the good air down there did not cure the condition and she died in 1890. David remained a widower then until 1893. He lived at 100 Westmoreland Road, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In that year on 28th October, 1893 he married Elizabeth Agnes Byrne of Chorlton cum Hardy in Lancashire. She was the daughter of a Commercial Traveller.

In August 1884 difficulties between China and France reached a crisis and the French fleet arrived at Keelung and bombarded the forts. Liu Ming Chuang, Governor General of Taiwan, had no intention of presenting the French with a well equipped mine and a large stock of coal and gave orders that the mine machinery should be destroyed, the shafts flooded and the stock of coal – some 15,000 tons – set fire. His orders were carried out immediately, ending modern mining in Taiwan for some time.